Rainstorms in Cayambe always came suddenly. The sun would often rise on a beautiful day with a sky unblemished by clouds, and, hours later, grayness would seep from the canyons of the surrounding mountains and hang over the valley. With a loud thunderclap, the sky would erupt with rain. If I was in a home with a tin roof, the pounding rain would reverberate through the house, and I couldn’t hear what my companion and those we taught were saying. During one storm, Cayambe’s streets turned into canals. We needed to cross the road, so I stepped in. Dirty rainwater reached my calves as we made our way to our appointment.

On Sundays, storms would often come one-half hour before church services started, and people wouldn’t come; they blamed the rain. But I understood. When your only means of transportation is your feet, walking fifteen minutes in a downpour to sit through three hours in a cold church isn’t very enticing.

After the rain stopped, it was usually dusk, and sunsets after a storm were gorgeous. There are two things in nature that will electrify colors: when the clouds part after a rainstorm, the humid air deepens the hues of every leaf, tree, and blade of grass, and when the sun is low in the sky, either in the morning or the evening, its rays glaze everything they touch with gold. When the two of them combine, like they did in Cayambe, the effect is magical. The mountains were vibrant greens, the valley glistened, and the pastel colors of Cayambe’s Spanish-colonial, adobe homes and buildings seemed more springlike. So when Utah’s rains mimic Cayambe’s, I close my eyes and return to Cayambe, a small, Andean city in Ecuador’s northern highlands.

An hour by bus from Ecuador’s capital, Quito, Cayambe rests on the east bench of Ecuador’s Valley of the Sun. Hundreds of years ago, the Cayambi Indians cultivated the valley, and when the Spanish conquistadores discovered it, they took the land, built haciendas, and subjugated the natives. Today, the Cayambis no longer exist as a people. Their Quichuan dialect has almost disappeared, and most Cayambeños are the decedents of Spanish and Native American progenitors. But in the mountain villages surrounding the valley, thousands of natives farm and live much like their ancestors, and their rectangular fields still ascend the slopes of green mountainsides to the east, north, and west of the valley.

And towering to the east of Cayambe is an extinct volcano: the Nevado. It gently rises from the city and gradually ascends to heaven. At fifteen thousand feet, its rich green foliage surrenders to shimmering snow. The mountain climbs several thousand more feet before the snow becomes sky. From Cayambe, the Nevado looks like a symmetrical, white bell skirted by green velvet. On clear days, the glacier would reflect sunshine, and the snow’s whiteness would intensify until its brightness seemed celestial. I have never seen anything so brilliantly white.

And when sunset would bathe the valley in its rosy hues, the Nevado would blush. Even after the sun had descended, the glacier would resonate pink for several minutes while shadows blanketed Cayambe and its countryside. But the Nevado’s beauty was not obscured with nightfall. When the moon was full, bluish moonlight would reflect from the glacier, and the mountain would glow.

Beneath this massive volcano, Cayambe and the Valley of the Sun blossom. They are the flower of Ecuador. Three minutes longitude north of the equator, Cayambe’s elevation determines its climate. And at 8,000 feet above sea-level, spring is eternal in Cayambe. The valley’s fertile soil is ideal for farming; green acres of alfalfa and corn and golden wheat fields checkerboard it.

Twenty years ago, Cayambe and its sister village Tabacundo were small settlements occupied only by those whose ancestors had lived there for centuries. But after someone discovered that the valley’s soil was perfect for cultivating flowers, the Valley of the Sun bloomed. Today, hundreds of plastic-covered greenhouses are interspersed among grain and alfalfa fields and glisten in the Ecuadorian sun. Flower cultivation is a multimillion dollar enterprise, and Cayambeño roses are exported throughout the world. If you watched Princess Diana’s funeral several years ago, you saw flowers grown on the Valley of the Sun’s plantations. And because one dozen roses only costs fifty-two cents within the town, Cayambe is the ideal residence for romantics and husbands who are in the "dog house."

The plantations also provide steady work and have attracted thousands of Ecuadorians hoping to encounter steady work in an economically troubled country, and Cayambe’s population is as diverse as the Valley’s flowers: Indians work beside Costeños (coastal people), Serranos (Mountain people), and Ezmeraldeños—decedents of African slaves who overpowered their ship’s slave traders off the coast of Ecuador and gained their freedom on the shores of South America.

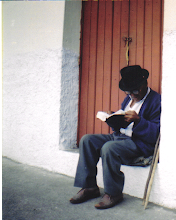

Most people wouldn't let us into their homes, so we talked to many of them in Cayambe's streets. Old men in dingy, dark sweaters and tailor-made slacks with either adjust-to-fit caps or narrow-brimmed hats which seemed to be from classic, black-and-white movies often sat together talking. I don’t know what they discussed; they never let missionaries near them. If we tried to talk, they simply reminded us that they were Católicos.

Old women, on the other hand, scared me to death. When we tracted, I prayed that an old woman wouldn’t open the door at every house we knocked. Whenever, a door opened and I saw a woman in a cardigan with silver hair pulled back into a braid, I braced myself. I considered myself lucky if I could spit out my companion’s and my name before the door would slam. It’s not that old women were mean people. They were only mean to LDS missionaries, and I never understood why. I always wondered why those women’s grandmotherly instincts didn’t kick in when they saw two young men, boys really, standing at their door. I’ve since thought about it, and I’ve realized that they didn’t reject us because of who we were; they rejected us because of what we represented: change. I’m certain that if they would have listened, we would have become friends, and they might have accepted our message. But they were trying desperately to maintain their way of life in a town which was becoming more different daily. I don’t blame them for wanting to hold onto what they loved the most.

Even though we experienced rejection from Cayambe’s elderly, younger couples would listen to us. When I was with my first companion in Cayambe, Elder Ortiz, whenever an appointment fell through, he beeped like a radar until he spotted a couple. At times, it was difficult to discern which were families and which were simply sweethearts. But if a young man or woman carried a baby or if a couple was holding hands, we would approach them.

Normally, the novelty of speaking with a gringo would hold their attention for a moment, and when we taught them that their families could be together forever, most listened intently, especially wives. They gave us their addresses, and we usually taught them three or four times. Sadly, work schedules, family problems, or the lack of interest ended our visits with each family. But they accepted the Book of Mormon, and about half read at least one chapter. I still pray for the Ramirez, Maygua, Hernandez, Lopez, and Farinango families. We found them all on the streets, and they each found their way into my heart. May God bless them.

It was hard to spend so much time in the streets. Although the temperature rarely rose higher than 75 degrees, the Caymbeño sun was intense. Because Cayambe is so high, there is less sun-filtering atmosphere to protect exposed skin and eyes. Elder Neff and I looked like lobsters for the entire time we were there. What was worse, canyon winds would stir up street dirt and lodge it in our eyes.

But the time in the street was worth it. I fell in love with missionary work in Cayambe, and I haven’t lost it. One preparation day, I was in our kitchen which had blue-tiled counter tops and a red, cement floor. I had a copy of the Brigham Young Priesthood and Relief Society manual. In it, Brother Brigham said that the desire to preach the Gospel burned in his bones. He could not be restrained. As I read his words, I realized that the same desire burned within me. I couldn’t stop, and, today, I am addicted to sharing the Gospel of Jesus Christ with others. It is a legacy passed down to me by the Prophets, and I hope to give it to my children. And I feel like Nephi when he said, "And we talk of Christ, we rejoice in Christ, we preach of Christ, we prophesy of Christ . . . , that [all] may know to what source they may look for a remission of their sins" (

2 Nephi 25:26). If I had never gone to Cayambe, I never would have felt it.

So when it rains in the springtime, I long for Cayambe. I can’t wait to return. I miss its people and dust-blown streets. Part of me wouldn’t mind to hear one of the colorful rejections which my companions and I received daily. At least I could talk to someone from Cayambe. One day, I will take my wife, daughter, and son to show them the Nevado. We will try to find the Mayguas and the Farinangos. And I will buy my wife a fifty-two-cent bouquet of red roses. Until then, I’ll have to watch rainstorms cover Utah’s runoff-greened mountains with misty clouds to ease my longing for my Andean home.